New Tool Assesses Risk in Acute HF Then Suggests Next Steps, Cutting Later Events

The hospital-based decision-support tool not only streamlined care but also significantly reduced subsequent admissions.

CHICAGO, IL—A hospital-based clinical decision-making support tool coupled with a rapid outpatient clinic follow-up protocol seems to lower the combined risk of all-cause death and cardiovascular hospitalization for patients with acute heart failure (HF) seeking emergency care, according to new data.

“Implementation of this approach may lead to a pathway for early discharge from the hospital or emergency department and improved patient outcomes,” said Douglas S. Lee, MD, PhD (ICES, University of Toronto, Canada), who presented the Comparison of Outcomes and Access to Care for Heart Failure (COACH) trial findings Saturday during a late-breaking clinical trial session at the American Heart Association (AHA) 2022 Scientific Sessions.

Not only did the strategy used in this study stratify patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk cohorts, but it also provided guidance to providers about what to do with that information as well as help navigate patients through the emergency room into a dedicated heart failure clinic for follow-up.

An intervention like this has immense benefit for “frontline providers who are tasked with triaging patients with limited data,” said Vishal N. Rao, MD (Duke University School of Medicine and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC), who commented on the study for TCTMD. “This tool may aid toward facilitating multispecialty care in guiding patients toward hospitalization or early follow up.”

There has been “a paucity of evidence around health service interventions to guide decision-making and care in the emergency department among those presenting with decompensated heart failure,” said Harriette Van Spall, MD (McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada), who discussed the findings following their presentation. Because of that “The research question fills an important knowledge gap.

“This has important implications for health-resource utilization,” she continued. “And once we have clarity on the process endpoints of patients admitted versus discharged in both groups, we will be able to assess overall healthcare utilization of this intervention.”

Intervention Effects

For the trial, Lee and colleagues enrolled 5,452 patients (mean age 78 years; 45% women) presenting to the emergency room at one of 10 Ontario hospitals with acute HF between January 2019 and December 2021. Notable exclusions included patients without a diagnosis of heart failure, those receiving palliative care, and those who were unable to complete follow-up care. Each of the hospitals were randomized in a stepped-wedge, crossover fashion from usual care (control phase) to the intervention. Upon entering the intervention phase, hospital staff had access to the web-based EHMRG30-ST calculator tool, which gave an assessment of whether patients had a low, intermediate, or high risk of death within 7 or 30 days according to vital signs and basic clinical information.

Per the study protocol, patients who were deemed to be low risk were encouraged to be discharged early and receive standard transitional care, while those marked high risk were recommended for hospital admission. Clinicians were asked to use their judgement for those at intermediate risk. Patients discharged early had access to standardized transitional care for up to 30 days in the Rapid Ambulatory Program for Investigation and Diagnosis of Heart Failure (RAPID-HF) clinic, which was staffed jointly by a nurse and cardiologist.

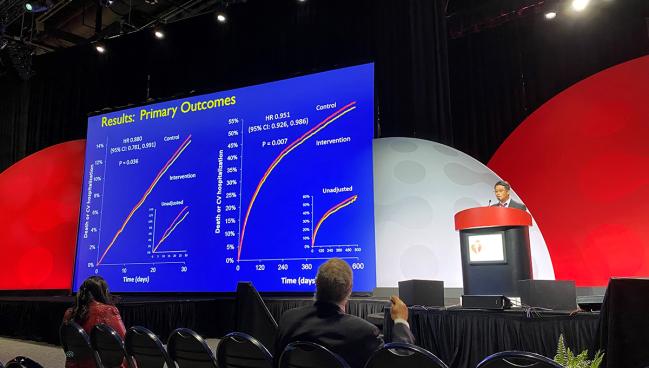

The intervention resulted in a reduction in the risk of death or cardiovascular hospitalization compared with controls at both 30 days (12.1% vs 14.5%; adjusted HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.78-0.99) and 20 months (54.4% vs 56.2%; HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.92-0.99). Differences in the secondary endpoints of cardiovascular hospitalization (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.76-0.93) and heart failure hospitalization (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.65-0.98) also were observed at 20 months.

“Our findings support the concept that not all patients who present to the emergency department with heart failure require hospitalization,” Lee and colleagues write. “Policy makers may consider appropriate discharge with rapid follow-up to be a viable alternative to hospitalization in some situations.”

The biggest limitations of their study, they say, include the inability to judge which exact components of the intervention had the greatest effect, the fact that the healthcare team was on a learning curve throughout the study period after the initiation of the intervention, the lack of data on racial/ethnic group for more than half of the population, and the lack of follow-up data for certain patients.

Other Scores

“The art of implementing a concise program like they've done here across multiple centers is truly impressive and is mostly can be limited by factors such as electronic health record [EHR], communication with providers, and also system-level agreement and prioritization of these conditions,” Rao said. While the tool they used did not include factors like ejection fraction or type of heart failure, he said those are sometimes harder to obtain in the emergency department setting and might not be needed for triage purposes.

Several risk tools have been validated for the estimation of both short- and long-term heart failure risk, including ASCEND-HF, Get With the Guidelines Heart Failure Risk Score, and the MAGGIC risk score, but their use varies, according to Rao. Studies like REVEAL-HF even have suggested no improvement in heart failure care or outcomes due to “alert fatigue” by certain EHR-based risk scores.

“A practical limitation is, one, being aware of the risk score and, two, knowing what to do with the output of the risk score with the patient in front of you,” he said. “It seems like this trial very effectively implemented a decision-tree pathway based on risk and provided guidance.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Lee DS, Straus SE, Farkouh ME, et al. Trial of an intervention to improve acute heart failure outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by the Ontario SPOR (Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research) Support Unit, the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research, the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, a Foundation Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care.

- Lee and Rao report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments