There is a bidirectional intersection of the nation’s top two killers that scientists want to better understand and disrupt.

There is a bidirectional intersection of the nation’s top two killers that scientists want to better understand and disrupt.

Cardiovascular disease and cancer often occur in the same people, potentially in large part because the two very common conditions share risk factors like obesity, which promotes inflammation, a key driver for both.

Medical College of Georgia scientists have mounting evidence that obesity also puts those with cancer at increased risk for cardiovascular disease and vice versa.

To make the intersection even messier, cancer treatment itself, while bringing patients and their doctors unprecedented success in quashing the devious disease, can increase the risk of cardiovascular disorders like high blood pressure, impaired heart function and unhealthy heart rhythms. It can even cause weight gain.

Scientists are less definitive about whether cardiovascular disease treatment does the same for cancer risk.

The intersection appears to be the busiest in Blacks, who have higher rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer as well as obesity. Still, the specific mechanisms that underlie the bidirectional risk between the top two killers, particularly for those of color, remain “undetermined,” MCG scientists say.

The American Heart Association has taken up this emerging field of cardio-oncology and its disparities as the focus of its newest Strategically Focused Research Network, and MCG is one of four centers nationally leading the new $11 million initiative which also includes Boston University School of Medicine, the Medical College of Wisconsin and the University of Pennsylvania.

“While the evolution of new therapies has improved the prognosis of many cancer patients, we’ve seen new challenges emerge as the very treatments that can cure people of cancer can also lead to short- and long-term cardiovascular (CVD) complications,” American Heart Association volunteer Dr. Kristin Newby, a professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham and chair of the AHA’s peer review team for the selection of the new grant recipients, said in announcing their new national focus in early Summer.

“There were more than 17 million cancer survivors in the U.S. in 2020, representing about 5% of the country’s population. Thus, the field of cardio-oncology has emerged as a critical new research area to address these concerns, as well as those related to findings that cancer itself can lead to cardiac disease, and the growing data suggesting that CVD and cancer share many common genetic, behavioral and environmental risk factors.”

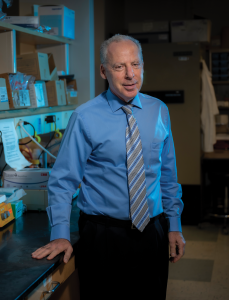

At MCG, the collaborative team of physician-scientists and frontline clinical investigators is working to better understand the bidirectional dynamic of the two common conditions, including learning more about how obesity and race contribute to each condition itself and to their intersection, says Dr. Neal Weintraub, chief of the MCG Division of Cardiology, associate director of the Vascular Biology Center and now director of the new AHA center.

Black Americans have higher rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer and death rates for these — as well as all major causes of death — are higher for Black Americans, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Black women have the highest rates of obesity or being overweight in the nation, according to the office, with about four out of five Black women affected.

“We are focused more on why, trying to understand the basis for the differences in cancer incidence and outcomes as well as for obesity and cardiovascular disease. We are looking specifically at obesity being a shared risk factor that is disproportionately affecting persons of color and this is due, we think to a combination of factors,” Weintraub says.

They want to better understand key dynamics such as how risk factors like obesity change the natural history of cancer development in Blacks with cardiovascular disease with the goals of better prevention, screening and potentially treatment.

There were more than 17 million cancer survivors in the U.S.

in 2020, representing about 5% of the country’s population.

Thus, the field of cardio-oncology has emerged as a critical new

research area to address these concerns, as well as those related

to findings that cancer itself can lead to cardiac disease, and the

growing data suggesting that CVD and cancer share many

common genetic, behavioral and environmental risk factors.

They are further exploring how socioeconomic disparities resulting from systemic racism, chronic psychosocial stress, and less access to affordable, high-quality food and health care can promote obesity. And how biological factors that regulate inflammation bodywide may contribute to the disparities that clearly exist in both these major killers.

“Once we better understand the causes, and especially the disparities, that might lead to individualized approaches. Personalized medicine is kind of a buzzword but in essence that is what we are talking about,” Weintraub says.

Better understanding includes conducting clinical as well as basic science research projects, like following patients with newly diagnosed prostate and breast cancer to look for early indicators that their cancer treatment is impacting their heart, and looking at genetic variations that may increase that risk.

Cardiologists like Weintraub see the impact in their patients, as studies at MCG have found a “very rapid decline” in the cardiovascular function of some patients with newly diagnosed cancer. While a cancer diagnosis is universally stressful, individual circumstances can make it even worse.

“If you don’t have a good solid job but you have to support your family and you don’t have a safe place to live, the compounding stress of having to take chemotherapy, we think, may be accelerating vascular aging,” he says.

So they are looking at that scenario and the individuals who find themselves in it, and also in the other direction. “We are looking at patients who are diagnosed with cardiovascular disease to try to understand their risk factors for cancer development,” Weintraub says. “Because frequently physicians treating these patients do not consider their risk for getting cancer, particularly African Americans. They suffer a greater burden of both of these diseases, and their outcomes are worse. We want to come up with interventions to change that disparity.”

With an eye on the scope of work ahead at MCG and nationally, the $2.84 million in funding awarded directly to MCG also is supporting three postdoctoral fellows focused on the field of cardio-oncology for up to two years with an emphasis on underrepresented minorities, with the ultimate goal of ensuring the next generation of scientists focused on these important health intersections.

In partnership with Paine College, a historically Black college and MCG’s neighbor, the center also has a research internship for up to six STEM undergraduates from Paine. Starting in this new year, the new partnership enables the undergrads to work directly with MCG clinicians, scientists and postdocs immersed in cardiometabolic disease research and treatment that broadens the students’ knowledge and hopefully inspires their interest in this emerging field of cardio-oncology that clearly, disproportionately affects Blacks, says Dr. David Stepp, vascular biologist and training director for the new center whose own research focuses on the cardiometabolic complications of obesity.

“We are moving from the side of them being afflicted to getting to the forefront and being part of the research,” says Dr. Anna-Gay Nelson, chemist and faculty chemistry advisor at Paine and undergraduate training director for the new center. Many of her students have parents or other family members affected by cancer, heart disease and/or obesity, Nelson ays, and many are also first generation college students.

Now Paine undergrads are taking a front row seat and role in explorations of the biological and environmental factors that put them and their families at increased risk. “Now we are trying to get ahead of it,” Nelson says, and giving back to the community in the process.

“We want to be there to support and help these students,” Weintraub adds. “By giving them this opportunity, we hope they will see what their aspirational goals can be. Why not say: I can be a physician-scientist.”

The four centers established by the AHA initiative will be collaborating as well, including putting their heads together on a $1.5 million network-wide research project that will also address disparities, a focal point for all the centers, Weintraub says. Boston University, for example, is studying the increased risk people with cancer have for developing blood clots to determine which cancers carry the greatest risk, the biological mechanisms causing the clots and how health disparities, such as race, living conditions and diet, contribute.

Inaugural cardio-oncology director

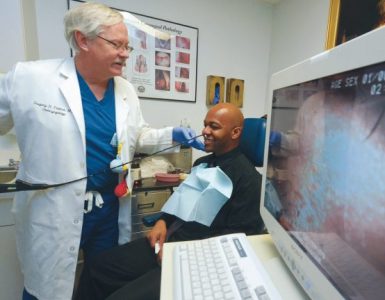

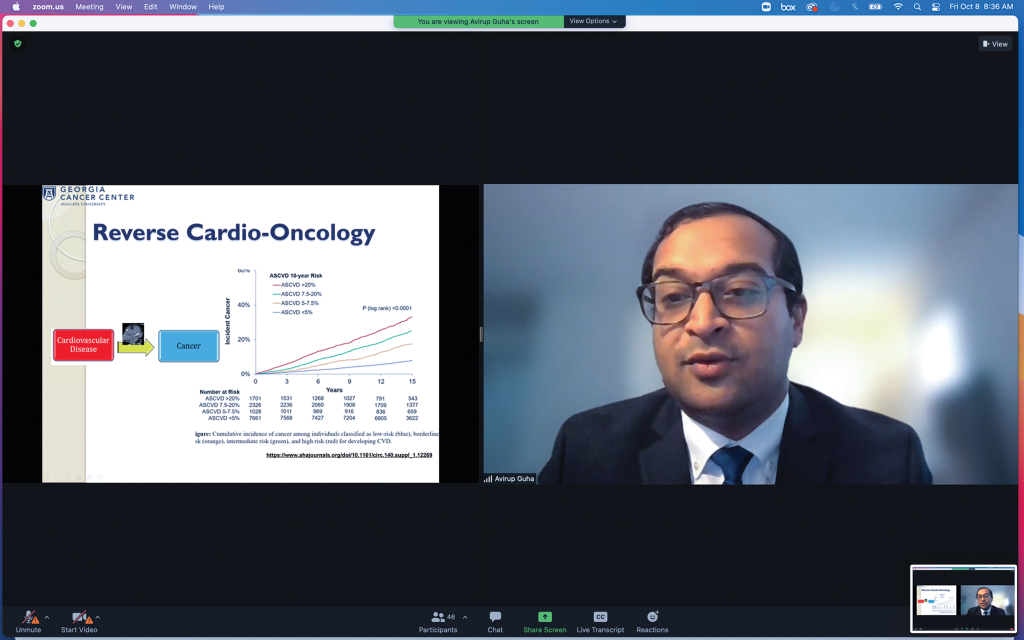

Closer to home and also starting with this new year, Dr. Avirup Guha, one of a relatively small number of board-certified cardio-oncologists in the nation who already made major contributions to MCG’s application for the AHA Strategically Focused Research Network center, is back at MCG as the inaugural director of cardio-oncology.

In Augusta he is starting a new clinic for this special subset of patients, and bringing new cardiovascular resources to the Georgia Cancer Center. He’ll also be developing a cardio-oncology telehealth network, which readily enables sharing of the expanding expertise at MCG with caregivers and their patients across rural regions, where racial, economic and geographic disparities likely are most acute.

The high-energy physician-scientist did his internal medicine training at MCG and its teaching affiliate AU Health System from 2012-15, during which he first connected with Weintraub — whose contributions he wants to emulate and whose energy he already does — worked with electrophysiologist Dr. Robert Sorrentino on clinical trials and trained alongside Dr. Paul O’Connor, renal physiologist in basic science before going to a cardiology fellowship at The Ohio State University. There he really began to see and make the connections between his specialty and cancer. Ohio State has a huge cancer center, which includes the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute. The cardiology service there kept getting referrals for patients at the cancer center, and there he met bone marrow transplant specialist Dr. Farrukh Awan. The two began to collaborate, including looking at how the drug ibrutinib, used for cancers like chronic lymphocytic leukemia, causes atrial fibrillation. Guha quickly grew an “organic” love for cardio-oncology, because it was a clearly important issue for patients and a nascent field in science and medicine in which he wanted to help fill in important gaps.

“Overall there is so much to be figured out as to how that happens, how in the process of fixing cancer, you can cause cardiovascular disease, and what we can do to prevent it. I mean, we know, for example, that people who have heart failure appear to be at a higher risk of cancer than those who do not have heart failure. That is a concept nobody would have even thought about a handful of years ago. Now there have been four or five papers in that field that all said the same thing.” But he notes that even today the evidence is largely observational, so more work needs to be done at places like MCG to really put these kind of pieces and risks together.

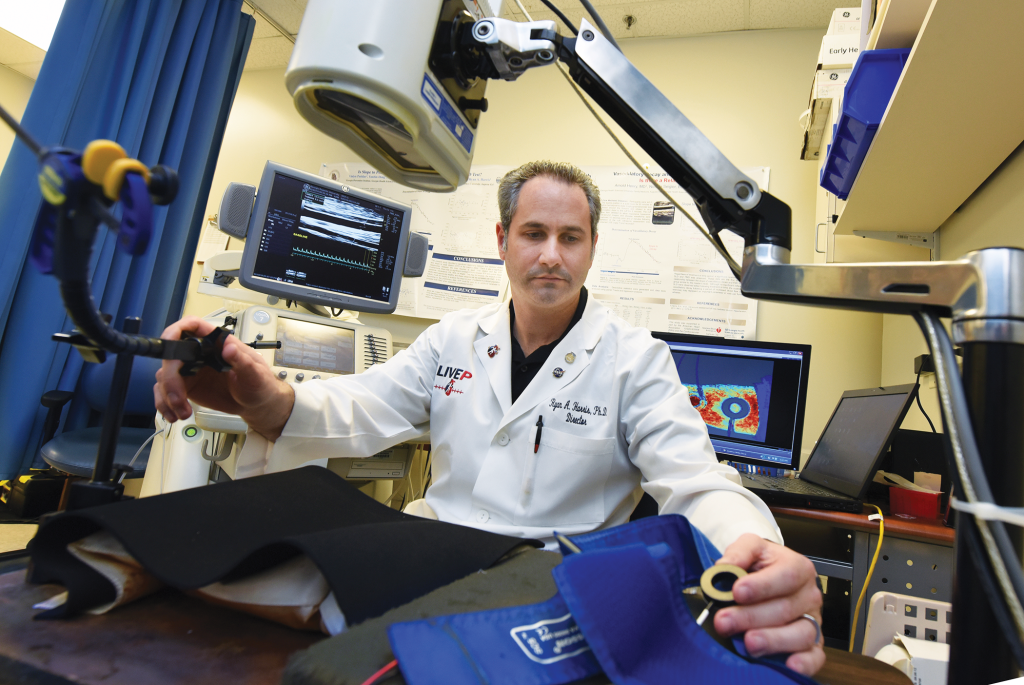

Some of his new work with Dr. Ryan Harris, clinical exercise and vascular physiologist at MCG’s Georgia Prevention Institute and principal investigator on the center’s clinical science project, will include looking at whether just getting cancer, not yet treating it, accelerates vascular aging. And, whether obesity in individuals with cardiovascular disease increases cancer risk compared to those who are not obese.

Guha also will be parsing complex topics like how disparities contribute. He notes the map of the expansive and largely rural state of Georgia and how a bigger health care presence tends to translate to better cancer and cardiovascular outcomes for regions like Atlanta and Augusta. Whereas rural areas tend to have less health care immediately available, incomes and educational levels tend to be lower as are access to the internet and good places to exercise, he says. Less affluent areas also still tend to correlate with a higher percentage of residents who are Black than white, Guha notes.

So he, Harris and their colleagues will be looking at the role of both structural elements like these and ancestry in their population science studies and how to realistically intervene where they can.

“We obviously try to improve quality and quantity of life by the medicine we practice and the science we do, but at the end of the day, one of the two —cardiovascular disease or cancer — is how Americans meet their demise,” says Guha.

“There are unmodifiable risk factors like age, which only go in one direction … and will always remain,” he notes, but there are modifiable ones too, like diabetes and high blood pressure, which can be prevented or treated and should be effective at preventing both common conditions.

“The research of how that is going to happen has yet to be done fully,” he says of the work to be done in his chosen subspecialty that the new AHA initiative should help kick-start, like those early indicators of vascular aging that he hopes Harris and his other colleagues will find.

His vision for his new home state is a National Institutes of Health-funded statewide cardio-oncology network that “will reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease as a barrier to effective cancer therapy and prolonged survivorship,” by directly working with caregivers and patients alike on a care plan that maximizes each patient’s outcome and reduces untoward complications.

Eventually, Guha, who was among those who helped the International Cardio-Oncology Society design questions for the cardio-oncology boards and was the only board-certified cardio-oncologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland before coming back to MCG, also wants to start a cardio-oncology fellowship in Augusta. “This is like a once in a lifetime opportunity.”

Look to people for answers

MCG’s Georgia Prevention Institute, led by Dr. Yanbin Dong, has decades of experience in longitudinal studies examining issues like why children grow up to be adults with heart disease and how fat contributes to cardiovascular disease. The Vascular Biology Center, which Dr. David Fulton leads, is a well-funded basic science engine that for a quarter of a century has been exploring the intersections of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Georgia Cancer Center, led by Dr. Jorgé Cortes, has already made inroads in getting the latest advances to patients regardless of geography as one of a dozen National Cancer Institute-funded initiatives providing minority and otherwise underserved patients with access to cancer clinical trials and treatment in their own communities. The new center has them putting their collective expertise together.

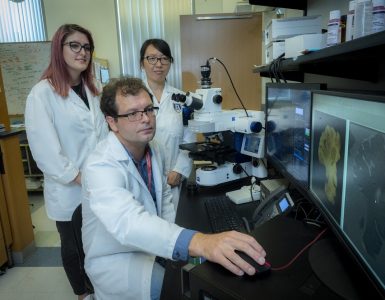

In the unique human-based studies underway, PI Harris is looking at newly diagnosed patients with breast or prostate cancer in collaboration with Dr. Zach Klaassen, urologic oncologist, and Dr. Priyanka Raval, hematologist-oncologist specializing in breast cancer, both at MCG and the Georgia Cancer Center. Harris’ lab is doing complex testing — like measuring arterial stiffness and skeletal muscle health — periodically across 12 months to assess the cardiovascular impact of cancer treatment as well as the stress of a cancer diagnosis.

“We know many risk factors are shared between cardiovascular disease and cancer, but after you get cancer, mortality and morbidity are accelerated in African Americans and those who are obese,” reiterates Harris.

A pilot study looking for any cardiovascular impact in patients with a recent history of breast cancer, which included 66-year-old Brenda Hoggard, diagnosed in 2020 with breast cancer, (see page 20), for example, indicated that levels of proinflammatory factors like TNF-α and IL-6 were more than twice as high in Blacks as whites and in individuals who are obese versus lean.

“We are looking at how vascular aging, inflammation and stress are affected over time after a cancer diagnosis,” Harris says. They want to better understand why Blacks have a greater cardiovascular impact and how, after a cancer diagnosis, adiposity affects vascular aging over time, he says of the studies that are following both adult Black and white patients with those social determinants of health, factors like stress levels and zip code, as a major focus.

“These projects within the clinical populations will allow us to start understanding where we could target these risk factors or these vascular health outcomes to try to reduce the burden after they do get cancer,” Harris says.

Raval, still early in her career, has already had some of her patients get cardiovascular disease, and is well attuned to the risks. Herceptin, for example, is a targeted treatment that changed the face of how she and her colleagues treat HER2 positive breast cancer, when patients have a surplus of these HER2 proteins, which normally help control the growth and repair of breast cells but in surplus can increase breast cancer cell growth and make the cancer tougher to treat.

“It’s changed the prognosis completely, so it’s beautiful, it saves lives,” she says. In fact, it was these kinds of great strides in treatment and her interest in taking care of women, that pulled Raval to cancer and breast cancer.

But sometimes there is a cost, and one of the established side effects is heart muscle damage and potentially heart failure. That means Raval monitors her patients’ hearts every three months, and when signs of trouble show up — most of these problems are considered reversible if caught early — there are protocols that include stopping the drug, at least for a while. Other drugs, like doxorubicin, are known to cause permanent heart damage. “When that happens, we have to unfortunately take a step back and think ‘Is it worth it? What is the risk-benefit ratio of these drugs versus the attendant cardiac risk,’” Raval says.

Heart-related risks like these tend to be rare, particularly in patients who don’t have other cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, she notes, and many of her patients are young, her youngest to date age 29, who was diagnosed while still breastfeeding her newborn.

But a significant number of her patients also are Black women, who may be slightly less likely to develop breast cancer, unless they are under age 45, than their white counterparts, but are more likely to have more aggressive disease, to get it earlier in life and to die from it.

So Raval talks openly and thoroughly over time with her patients who already have so much information and stress to deal with, encouraging all her patients to see their primary physician regularly, and get lipid profile checks. She will sometimes broach the tough topic of lifestyle modification needed to help address known risks, like excess weight, particularly around the waistline. Another irony/compounding factor is that some of the endocrine therapies used for hormone positive breast cancers, by far the most common type of breast cancer, can cause weight gain.

“You don’t want them to just live longer,” Raval says. That is why she joined the cardio-oncology initiative, which she hopes will yield still more definitive information, like identifying future trouble at the molecular level, before any outward signs show up, and further sharpen the eagle eye she already has for cardiovascular and other treatment complications.

“We have to be holistic in our approach. We cannot treat the symptoms or one part of the body, we are treating the whole patient and there are implications for the whole body of what we do,” she says including the understandable associated mental stress of a cancer diagnosis, which can worsen chronic inflammation and strengthen the bidirectional intersection.

A broad look

Coming from the other direction, extensive databases like the NHANESMedicare cohort are being used to parse population health issues and help gain insight on whether people who have cardiovascular disease also are at increased risk for cancer, not necessarily because of their cardiovascular treatment, but because of common risk factors for both conditions, says Dr. Xiaoling Wang, genetic epidemiologist at the GPI and co-PI along with Guha on the population studies.

This project is called reverse cardio-oncology because they are looking at the less-explored direction of cancer risk in people with cardiovascular disease in a prospective way, says Wang. Like their basic science colleagues, they also are looking at a mutation of the DARC gene, which is common in Blacks, and what role it may play.

DARC, or Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines, is a receptor on red blood cells, and about 70% of Blacks, have a mutation that eliminates DARC expression from those red blood cells, which in addition to their well-known role of carrying oxygen, also have a key role in regulating inflammation.

As part of their basic science pursuits in the new center, Weintraub and his colleagues are pursuing their early evidence that this common DARC mutation in Blacks impacts their susceptibility to both cancer and cardiovascular disease. In fact, their DARC knockout mouse has similar indicators of the predispositions, like higher levels of chronic inflammation. On a high-fat diet, the knockout mice’s fat tissue becomes more inflamed and they become more ill, says Weintraub, noting that tissue inflammation is important to the pathogenesis of many cancers.

The MCG scientists hypothesize that obesity and socioeconomic disparities, in concert with the loss of DARC’s usual role in controlling inflammation, lead to increased obesity and inflammation in Blacks and heightened risk for both cancer and cardiovascular disease. The DARC mutation likely also reduces the efficacy and increases the toxicity of cancer treatment in these individuals, Weintraub says.

Better answers

The Herbert S. Kupperman Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Science and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar, a native of Albany, Georgia who joined the MCG faculty in May 2013, remembers in medical school at Tulane University, hearing about “the red death,” one of the nicknames for the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, which mixes up red in the infusion bag and its many uses include treating breast and ovarian cancers. But its potential side effects include cardiomyopathy and heart failure, and, like Raval, Weintraub has seen a lot of young women with heart complications, including some who died. He also saw and early on began to study radiation-induced cardiovascular disease, although he notes that the now precisely focused beams of radiation have reduced but not eliminated this potential path of damage.

Stopping treatment is not the best answer to stopping these kinds of consequences, Weintraub says.

But solid science and experts who know what to look for, who have the imaging equipment and expertise needed to identify early, subtle changes in heart function and can help make the best decisions on whether a break or a change in treatment are in order, should be.

“We want to call attention to this so people are aware that if you have one disease you are at risk for having the other,” he says. “We want to really reveal this problem, then try to attack it.” Weintraub, who does not tend toward enthusiastic expression, only enthusiastic action, says being part of this important AHA national collaborative against the nation’s top two killers and for those most affected by them, is an honor.

“The level of competition was intense. We beat out some of the very best places in the country to become part of this network. I am very proud of this institution and the people here for what they have accomplished and will accomplish.”

Fundamentals

Breast and prostate cancer stand out among the most common cancers in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute. Prostate, lung and colorectal cancer make up about 43% of cancers in males diagnosed in 2020. Breast, lung and colorectal cancer accounted for about 50% of all new cancer diagnoses in women in 2020. As of January 2019, there were nearly 17 million cancer survivors in the U.S., a number that was expected to reach 22.2 million by 2020.

Within five years of diagnosis, individuals treated for lymphoma or breast cancer are three times more likely to develop heart failure as people who never had cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

Blacks have higher rates of cardiovascular problems like hypertension and ischemic stroke as well as some cancers, and their death rate from these conditions is significantly higher.

Black women with breast cancer had a 42% increased mortality rate and Black men with prostate cancer had four times the heart disease risk.

Increased adiposity increases breast cancer prevalence and Black women are about 50% more likely to be obese than their white peers.

A review article published in 2021 in the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine by key players of the MCG cardio-oncology team highlighted evidence about the role of obesity related disparities as well as mutations in the DARC gene, also known as ACKR1, in the bidirectional risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

The late Dr. Ross Gerrity, experimental pathologist at MCG, did some of the pioneering studies associating cardiovascular disease, diet and inflammation. He had worked with the swine model for atherosclerosis since 1973; and among his findings was the fact that scavenger white blood cells called monocytes, which migrate into artery walls and ingest excess fat with the idea of removing it, apparently become overburdened in the face of a prolonged high-fat diet. So instead of removing fat from the walls, they overingest, becoming lipid-laden foam cells — the hallmark of atherosclerosis — and eventually die in the vessel wall. “Subsequently it’s been demonstrated that the same type of thing occurs in the human,” Gerrity said in 2001. He died in 2008.